Old Aesthetics New Waves

- minalnaomi

- Nov 28, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 30, 2025

Over the past year of engaging with the European cultural sector in Amsterdam, I have observed a pronounced institutional effort to confront and redress the racialised histories embedded within their collections. Museums appear keen to rethink their narratives, foregrounding the structural violence and exploitation that underpinned the accumulation of their holdings. At the Mauritshuis, for instance, exhibition texts now acknowledge that the institution’s wealth was built through the transatlantic slave trade. The Wereldmuseum’s Our Colonial Inheritance similarly demonstrates this shift, reflecting an attempt to critically re-engage with colonial histories. Yet, despite these initiatives, I found that my own lived experiences and the embodied realities of people like me remained largely absent from these retellings - a dynamic that resonates with Spivak’s (1988) argument that institutional corrections often fail to transform who is authorised to speak.

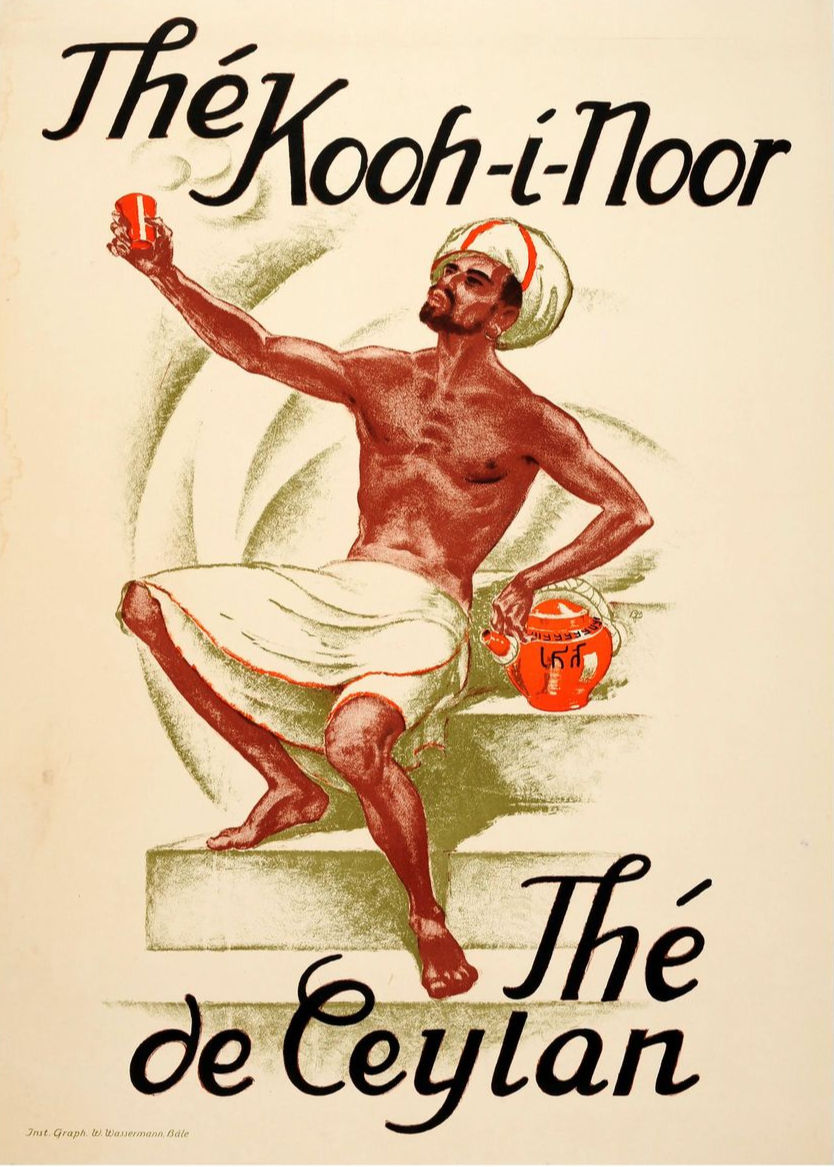

The ongoing legacy of extraction - its historical manifestations and contemporary repercussions - remains insufficiently examined. While certain aspects of colonial rule, particularly in Southeast Asia, receive institutional attention, the histories of South Asia are comparatively marginalised. To illuminate these gaps, I draw on a small collection of historical posters (that I found online) that exemplify how brown bodies - in this case, Ceylonese bodies - were constructed for a European gaze. This aligns with Said’s (1978) analysis of Orientalism as a system of representation that produces the colonised as exotic, knowable, and subordinate.

Rotterdamsche to Colombo

Image source - 1

A notable feature of these posters is the representation of women. They frequently depict smiling, sari-clad women engaged in acts of service. The imagery is repetitive: a woman holding a tray, her expression fixed in a somewhat vacant grin, eyes glazed over. Such representations illustrate Hall’s (1997) argument that meaning is produced and normalised through repeated visual codes.

Thé de Ceylan Le Lion Le roi des Thés, Le thé des Rois vers 1900

Image source - 2

Sumangala The

Image source - 3

Air Ceylon Sapphire Service

Image source - 4

Air Ceylon

Image source - 5

However, what lies behind these smiles warrants deeper interrogation. As a Sri Lankan, I recognise the socio-economic pressures that render smiling not merely a cultural trait but a strategic necessity. With tourism constituting a significant component of the national economy, Sri Lankans are compelled to perform hospitality within an unequal global marketplace. This dynamic mirrors Bhabha’s (1994) notion of mimicry, in which the colonised subject performs an expected role in ways that are simultaneously compliant and ambivalent. I sit with these realities and recognise them in my own interactions over the past year.

Image Thé Kooh-i-Noor Thé De Ceylan

Image source - 6

These unequal relations carry material consequences. Increasing numbers of locals are priced out of leisure spaces - beaches, cafés, and coastal restaurants - that once formed part of everyday life and vacation plans. Many Sri Lankans now feel hyper-visible and out of place in these settings, sentiments reinforced by establishments that have even displayed signs reading “No locals allowed.” Such exclusions reflect what Mignolo (2011) terms the coloniality of power, where global market forces reproduce historical hierarchies.

Goodnight Ceylon, Galle Fort Nighttime (1930s)

Image source - 7

These tensions surfaced acutely in Ahangama, a trendy new coastal town overrun with sun worshippers, European yogis clad in Lululemon, matcha lattes, oat milk and surf culture. Further up the coast in Unawatuna, a party organised by foreign residents required “white face” for entry. The event - hosted by individuals who often overstay visas and operate outside legal frameworks - was defended online as a space for travellers to mix and mingle.

(Conversely, I recall the 10,000 calls I must make to Naturalisation services, how my passport is always held under a magnifying glass and light at the border, and how I am invariably questioned about my intentions when arriving in Europe). The subsequent backlash led to its cancellation. Yet the broader reality remains: many Sri Lankans increasingly experience exclusion within their own coastal regions, which now cater primarily to foreign visitors and affluent urban elites who can buy a seat at the table. This echoes Fanon’s (1952) analysis of internalised hierarchies, where colonial value systems continue to structure who belongs and who does not.

I encountered this personally in 2020 while working along the coastline, when foreign residents questioned my presence: “Aren’t you …like…. from Colombo?” Their tone signalled an implicit hierarchy, reinforced by certain Sri Lankan urban migrants who adopted “alternative lifestyles” aligned with Western expectations of servitude. This dynamic recalls Bhabha’s (1994) discussion of hybrid cultural performances that reproduce colonial logics rather than destabilising them.

Ceylon Holiday Season

Image source - 8

The Chinbara Poster By Daniel De Losques 1900 Iconic French Impressionist Art Vintage Tea Advertisement Featuring Early 20th Century Design

Image source - 9

The unfortunate truth is that most of these soft-colonial tools are still in place. Some call this neo-colonialism. The kind of dynamics that ensure that Sri Lankan’s are still subservient to people from the West. That whiteness is held at a superior position and somehow these people are always seen better, prettier, more worthy and certainly more intelligent. I reflect on how I found myself tongue-tied for the first two weeks of sitting in my first ever international classroom in Amsterdam - thinking that I wasn’t worthy of speaking up since I knew that my classmates from Europe probably had a better education, and therefore had more intelligent things to say. Forget my 13 years of work experience (which I stumbled over when I was asked to speak of my past experience) - this room of twenty-somethings straight after their Bachelors surely knew better. Worse was listening to them lament about how tough it was to earn a decent wage - meanwhile, I always stationed myself next to my Surinamese classmate, a journalist with many, many years of work experience under her belt. There were certain solidarities that needed no words - just quiet recognition in each other's lives.

What irked me more, was on my trip back to Colombo from my week away by the ocean, was a moment when I wandered into a tourist shop in the Galle Fort. This store framed images of old colonial era Ceylonese posters - the kinds you find in most Air-bnbs, and small boutique properties dotted along the coastline. I stood there - floored - at how many of these old posters had been reinterpreted for a newer tourist gaze or an unassuming local that might need a lot of unlearning. These images still bore women in subservient positions. They exoticised these women and more infuriatingly - these women now bore pottus or bindis - symbolising their otherness. These re-articulated images reflect the ongoing relevance of Said’s (1978) argument that Orientalist aesthetics persist through modern cultural production.

Pay close attention to the names of the cards and the art direction. These are either contemporary designs or modern day reproductions.

Uncle Al, Ceylon

Art Direction: P.J.B; Ilustrator: Alexey Kot

Postcard from from Stick No Bills, Galle Fort

Blue Star Winter Cruise to Ceylon, SS Arandora Star, London, 1935

Postcard from Stick No Bills, Galle Fort

Picking Empire Tea, Empire Marketing Board 1930,

Art Direction: Harold Sandys Williamson

Postcard from Stick No Bills, Galle Fort

One poster depicted foreign women at the beach being approached by local “beach boys” - young Sri Lankan men offering surf lessons or companionship. Such imagery reinforces long-standing hierarchies in which whiteness functions as the desirable centre, while local men and women remain positioned as service providers or exoticised bodies. This visual economy exemplifies what Hall (1997) terms the power-laden production of meaning within representational systems.

Surf of Sri Lanka, Weligama Bay, Sri Lanka

Art Direction: Phillip James Barber; Illustration : Maria Pavlikovskaya

Postcard from Stick No Bills

These examples invite a broader question: is colonialism truly past, or do contemporary market structures, particularly in tourism, continue to reproduce colonial relationships under new guises? The posters - whether preserved as artefacts or reimagined for modern consumption - serve as visual reminders of a continuing aesthetic regime. They represent a new wave of old aesthetics. Read through Mignolo’s (2011) framework, they illustrate how coloniality persists within global capitalism. Neo-colonialism thus remains deeply embedded in Sri Lankan tourism, masked by hospitality, commodified smiles, and the ubiquitous offer of tambili (fresh coconut water).

Reference List

Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The location of culture. Routledge.

Fanon, F. (1952). Black skin, white masks. Grove Press.

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. Sage.

Mignolo, W. D. (2011). The darker side of Western modernity: Global futures, decolonial options. Duke University Press.

Said, E. W. (1978). Orientalism. Pantheon Books.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press.

Image Sources

https://bintphotobooks.blogspot.com/2014/11/ceylon-sri-lanka-lionel-wendt-h-arnoux.html

https://www.iloveceylon.com/product/postcards/sumangala-the/

https://www.iloveceylon.com/product/vintage-posters/air-ceylon-stewardess/

https://www.kapruka.com/buyonline/the-chinbara-poster-by-daniel-/kid/ef_pc_home0v2063pod00009

Comments